Goals for 2018-19 School Year

Our workgroup met Tuesday evening to walk through our goals for the 2018-19 school year which are focused on getting Number Talks to take root within schools.

- Validate assumptions about what needs to be in place for Number Talks to take root and spread within a school

- Pilot effort with Brown Street Academy and Prince of Peace

- Recruit and prepare additional educators in round 2 schools

- Develop community of practitioners that can support pilot and round 2 schools

Assumptions

Our assumptions about what needs to be in place for Number Talks to take root and spread within a school come out of our workshop at the Systems Thinking Institute in March, and our ongoing work with educators involved with the project.

Support

- Overt support of building leadership

- Community Partners (Learn Deep, Milwaukee Succeeds, UWM)

Resources

- In-building expertise/support for Number Talks in a role that can serve classroom teachers

- Willing cohort of teachers

- Time for in-building collaboration

- Cross-school network of practitioners willing to share problems and ideas

- Peer-based professional development

Tools

- A shared set of tools teachers can use in their practice:

- Common Terms

- Sentence Starters

- Anchor Charts

- etc.

Collaborative Feedback Processes

- In-building

- Cross-school/district

Pilot School Criteria

Our assumptions about what is required for Number Talks to take root and spread, guide our criteria for where it makes sense to pilot the effort:

- Supportive Building Leadership

- In-school resource in a role that can support colleagues working to establish Number Talks as a regular practice.

- 3+ teachers willing to establish Number Talks as a regular practice within their classrooms from the start of the school year.

- Participants willing to collaborate across school/district boundaries

We’re excited to be able to pilot the effort with Brown Street Academy (MPS) and Prince of Peace Elementary School (Seton Schools), and will be working with both schools over the summer to prepare for a fall start.

Tools

A number of the tools teachers planning to implement Number Talks are looking for were produced and archived as part of the GE Foundation project within MPS. These include:

- Sentence Stems

- Discussion Prompts

- Math Strategies

- Planning Guide

- Teacher Moves

These tools, and others are available on the project’s legacy site:

https://sites.google.com/milwaukee.k12.wi.us/gefvideos/math-resources

In our work this year, we also saw the need for a couple of additional tools– first, what we’ve been calling a Strategy Map– a quick guide for teachers that, for a given Number Talk, gives them a sense of the types of strategies they might see, common errors, and for those common errors, strategies a teacher can use to allow students to recognize and correct the error. We’ll explore what these might look like over the summer.

We’ve also heard a need for a tool that can allow a teacher easily note where a student is in their thinking or level of comfort with a strategy that does not disrupt the flow of the discussion. A simple checklist may suffice and we’ll look to test out some options within our pilot schools.

Collaborative Feedback Process

In-Building

For teachers to quickly develop competence and comfort in a new practice, effective, timely feedback is key. We envision a process that borrows from Scrum, an agile methodology used in software development. The idea here is a quick daily meeting that allows team members working on a common project (in this case Number Talks) to communicate where they are, where they are headed, and what they need help with. Our suggestion is to do these on the same frequency as Number Talks, 3-5 days a week.

Cross-school/District

For the 2018-19 school year, our workgroup meetings will shift towards peer-based professional development. We look to continue the schedule of meeting every 4 to 6 weeks, but the focus will be on what teachers see, learn, and need help with as they use number talks in their lessons. We’ll expand the group to include not only the teachers at our pilot schools working with number talks, but teachers at other schools that are using the practice on their own, or from schools that are looking for more widespread use.

Role of Community Resources

Throughout the year, we’ve had help from Kevin McLeod and Gabriella Pinter from UWM’s Mathematics program. UWM has a couple of professional development opportunities this summer, that Brown Street teachers will take advantage of in preparation for the work they will be doing next fall.

Strong Start Math Project — June 18-29

Early Math Seminar — July 30 – August 3

We touched briefly on the potential to connect after school programming at the Boys & Girls Clubs to the work schools are doing around Number Talks, as well as leveraging the Milwaukee Area Math Council to reach additional teachers interested in bringing the practice into their schools.

Metrics & Evaluation

As we look to scale the use of Number Talks within schools, we see the need for two sets of metrics. The first, is focused on the spread of the practice:

- Number of teachers using Number Talks as a regular practice

- Number of schools with teachers using Number Talks as a regular practice

- Number of students participating in Number Talks on a regular basis

- Frequency of Number Talks for teaches, schools and students

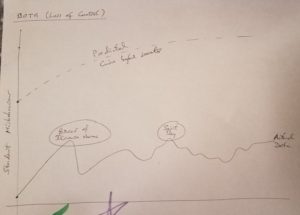

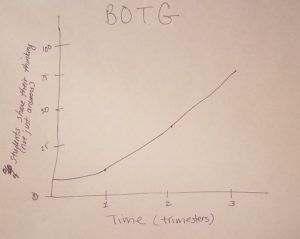

The second set of metrics is aimed at evaluating the effectiveness of the program. There we can look not just at test scores, but

- Movement along learning trajectories/where students are in their thinking

- Level of participation in discussions

- Improvements in classroom culture

UWM’s Master of Sustainable Peacebuilding Program put together a workbook of tools that MPS might use to assess them impact of Systems Thinking in Schools. They see that Systems Thinking training ought to have impacts beyond simple mastery of of the ideas. As those ideas are put to use by students and staff the impact should be felt in the culture of the school, how students deal with conflict, etc. Given that number talks establish a pattern of respectful discourse where the students’ ideas are valued, we expect the practice to show impacts beyond understanding in math, and that a similar approach could be useful in assessing the effectiveness of Number Talks.

Next Steps

As we look forward to our fall pilots with Brown Street Academy and Prince of Peace, we’re moving on to what we need to get done over the summer:

- Get the resources/tools in place for pilot teachers

- Identify schools/teacher leads for who are interested in following the pilot efforts/participating in next year’s work group series

- Confirm roles for community resources

- Solidify the evaluation process

- Secure funding to support the effort

If you’d like to join or support the effort, please let us know.

In our May session we explored several issues around creating effective STEM internships for high school students. We began the evening with a review of

In our May session we explored several issues around creating effective STEM internships for high school students. We began the evening with a review of  Problem:

Problem: Our April Collab Lab focused on the opportunities we can create for students by engaging partners in the neighborhoods which surround a school. The goal was to explore how we might: engage students in real-world projects with organizations, businesses, and community members in the neighborhoods which surround a school; leverage then enthusiasm and energy of students working on problems they care about; foster relationships that allow for sustainable engagement over the long term.

Our April Collab Lab focused on the opportunities we can create for students by engaging partners in the neighborhoods which surround a school. The goal was to explore how we might: engage students in real-world projects with organizations, businesses, and community members in the neighborhoods which surround a school; leverage then enthusiasm and energy of students working on problems they care about; foster relationships that allow for sustainable engagement over the long term.

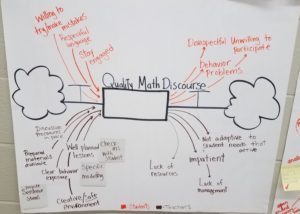

The focus for our workgroup is now shifting to explore how we can speed the adoption of meaningful discourse/Number Talks within schools. If we want to scale an effective practice, we need to get beyond simply asking (or telling) teachers to use the practice because it is effective. As teachers plan their lessons, they need to balance a number of competing forces. For Number Talks to be part of their solution, we need to understand those forces, and set up the conditions where the regular inclusion of Number Talks becomes the easy choice for them to make. This will be the focus of our two day workshop at the

The focus for our workgroup is now shifting to explore how we can speed the adoption of meaningful discourse/Number Talks within schools. If we want to scale an effective practice, we need to get beyond simply asking (or telling) teachers to use the practice because it is effective. As teachers plan their lessons, they need to balance a number of competing forces. For Number Talks to be part of their solution, we need to understand those forces, and set up the conditions where the regular inclusion of Number Talks becomes the easy choice for them to make. This will be the focus of our two day workshop at the  What do you hope will happen when you implement math discourse in your classroom?

What do you hope will happen when you implement math discourse in your classroom? What do you fear will happen when you implement discourse in your classroom?

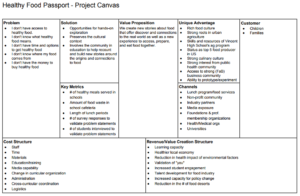

What do you fear will happen when you implement discourse in your classroom? At this session, we used a version of the Lean Startup Canvas to guide our thinking and capture our assumptions about the goals for the project, and how it might be structured. We started the process with a discussion of the problems we are trying to address through the project, and then stepped through the remaining sections of the canvas. We closed with a discussion around the importance of starting with validation of the key assumption– that the problems we identified matter to the students engaged in the project. The end result is available here:

At this session, we used a version of the Lean Startup Canvas to guide our thinking and capture our assumptions about the goals for the project, and how it might be structured. We started the process with a discussion of the problems we are trying to address through the project, and then stepped through the remaining sections of the canvas. We closed with a discussion around the importance of starting with validation of the key assumption– that the problems we identified matter to the students engaged in the project. The end result is available here:

During Collab Lab 16, we walked participants through our model and had them beat up the idea in both small group discussions and a sharing out of key points to all participants.

During Collab Lab 16, we walked participants through our model and had them beat up the idea in both small group discussions and a sharing out of key points to all participants. We thought we’d try and find some. Last night we pulled educators from across the area together with healthcare researchers and professionals. We asked Brian King, a Collab Lab regular and former Director of Innovation for the Milwaukee Jewish Day School to facilitate. Brian’s work with students to develop and launch student run projects with a social purpose help make him the right person to guide the group through what we wanted to accomplish. In short, to generate ideas for projects that:

We thought we’d try and find some. Last night we pulled educators from across the area together with healthcare researchers and professionals. We asked Brian King, a Collab Lab regular and former Director of Innovation for the Milwaukee Jewish Day School to facilitate. Brian’s work with students to develop and launch student run projects with a social purpose help make him the right person to guide the group through what we wanted to accomplish. In short, to generate ideas for projects that: Participants started the evening with some Post-It Note brainstorming on the top five health related issues faced by school-age children. Three volunteers grouped these by topic. We talked through each cluster, did a bit of rearranging and pulled out our blue dots for a vote on which topics were most important.

Participants started the evening with some Post-It Note brainstorming on the top five health related issues faced by school-age children. Three volunteers grouped these by topic. We talked through each cluster, did a bit of rearranging and pulled out our blue dots for a vote on which topics were most important.

In September we took the equipment we had left to Maker Faire where we were mobbed for three days by kids wanting to take stuff apart. A number of educators who stopped by the booth asked if we could do something like this at their school.

In September we took the equipment we had left to Maker Faire where we were mobbed for three days by kids wanting to take stuff apart. A number of educators who stopped by the booth asked if we could do something like this at their school. Last Tuesday we went out to Thurston Woods where students took apart DVD drives, a circular saw, printer, keyboard, camera, and a few other odds and ends in our collection. Today we were out at Browning Elementary to do more of the same. We were thrilled to see the students dive in and work together with little more instruction than “righty-tighty, lefty-loosey”.

Last Tuesday we went out to Thurston Woods where students took apart DVD drives, a circular saw, printer, keyboard, camera, and a few other odds and ends in our collection. Today we were out at Browning Elementary to do more of the same. We were thrilled to see the students dive in and work together with little more instruction than “righty-tighty, lefty-loosey”.