In our work with schools over the past 4 years we’ve noted some key gaps in experiences and skills that limit what students are able to accomplish on K-12 engineering projects. We’ve also noticed that pulling in the resources that can support students as they take on more complex work is much easier when there’s a chance to see students do great things.

There are systems in place that allow kids coming out of high school to perform at a very high level in music or sports.

What if we did the same for engineering?

At Learn Deep we see the potential for a great K-12 farm system to develop diverse engineering talent in Milwaukee and want to get that moving as a collaborative effort. On Tuesday, we took the first step by convening a working session that included K-12 educators, engineering faculty, industry mentors, and organizations with STEM/engineering programming for K-12 students. As a group we used that session to identify the gaps in skills and experiences that slow their development of talents useful in engineering.

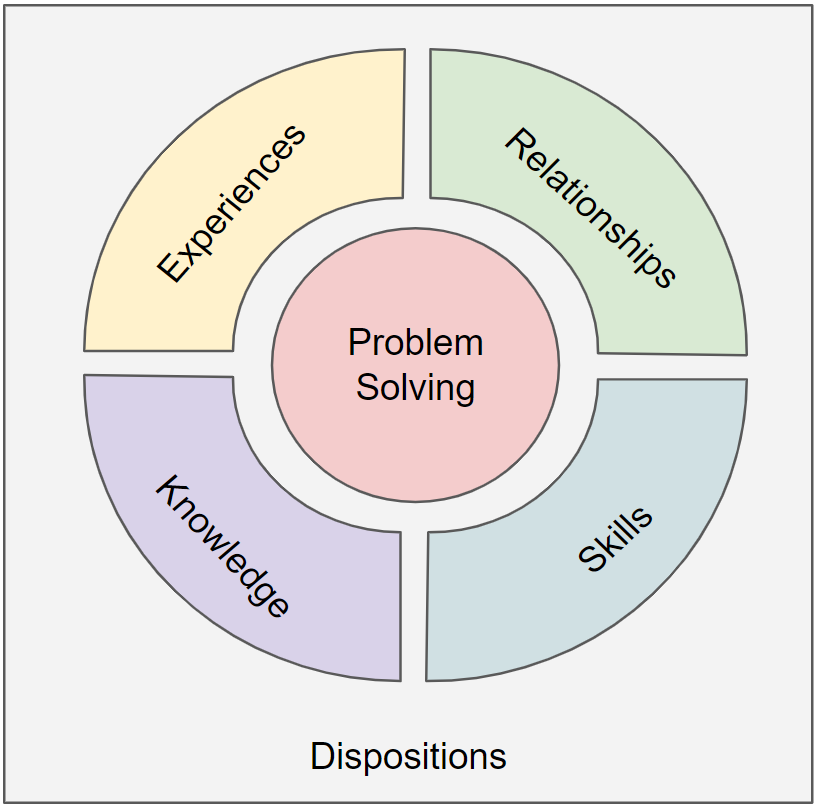

What makes for an effective problem solver?

We put together the diagram here a few years ago as we pondered this question. Effective problem solvers draw on each of these 4 areas:

Experiences

What does this problem remind me of?

- How I felt

- How people reacted

- What worked

- What didn’t work

- etc…

Knowledge

What knowledge can I bring?

- Math

- Technology

- Design

- Psychology

- History

- Tools are appropriate for a problem like this,

- etc…

Relationships

Who do I know that can:

- Support me

- Provide guidance/advice

- Connect me to others

- Act as a mentor

- etc…?

Skills

What skills can I bring?

- Analytical

- Creative

- Communication

- Collaboration

- Prototyping

- etc…

Dispositions

I bring:

- Curiosity

- Grit

- Growth mindset

- Openness

- etc…

We have been using this insight in the development of many of our projects to date, including our unique Zoo Train Engineering project.

What would we like to see as students develop talents that are valued in engineers?

Not surprisingly, this structure works pretty well for talking through what we heard from the group.

Experiences

- Building things

- Working with tools

- Working with materials and other resources

- Designing solutions for real world problems

- Using mathematical reasoning to flesh out and evaluate design options

- Working as part of a team

- Problem solving in a context that emphasizes process over results

- Working alongside a college student or professional to understand how they approach engineering challenges

- Presenting their work to an authentic audience

Knowledge

- Comfort with introductory statistics

- “Calculus ready” math knowledge by high school graduation

- Physics

- Understanding of how materials go together

Relationships

- Knowing an engineer that “looks like me”

- Feeling part of a team

Skills

- Spatial thinking

- Effective time management

- Able to listen to and understand a customer’s needs

- Able to use empathy and observation to identify or understand a problem someone else has.

- Able to build a solid understanding of a problem before jumping to solutions

- Able to effectively communicate one’s ideas

Dispositions

- Able to self direct learning

- Willingness to explore “risky” options

- Having a sense of ownership of one’s work

- Resourcefulness — willing to seek out help or other resources to gain understanding

- Willingness to accept “failure”– e.g. recognize that a solution does not work and learn from that.

- Willingness to recognize that the first, last, or their own idea for a possible solution may not be the best approach

- Problem seeking — willingness to see out problems that might be interesting to solve

What do effective farm systems in other domains look like?

In preparation for the session we pulled together the following table, which sketches out the formal and informal opportunities students have to develop their talents in sports and music. As one ponders what a farm system for engineering talent might look like, one question that jumps out to us is where are the opportunities for play, and are they available to students who’s families may not have the resources to provide materials which can allow that to happen.

| Setting | Sports | Music |

| Informal play | Pick up games with friends/family, might include a mix of ages; no requirement for full field or team–e.g. play with what and who you have availableNo emphasis on practice, but one might get some informal coaching/feedback from other participants during play (“nice pass”, “next time you are doing that, look for…”) | Play alone or with friends/family. Might include a mix of ages; no requirement for specific combination of instruments–e.g. play with what and who you have available.No emphasis on practice, but one might get some informal coaching/feedback from other participants during play (“nice lick”, “next time you are doing that, look for…”) |

| Informal practice | Practice skills on one’s own or with friends/family | Practice skills on one’s own or with band mates |

| School class: play + practice | Major focus is on play, with some practice of skills | Major focus is on play, with some practice of skills |

| School team/group or development program: focused practice + play | regular practice aimed at skill development regular play as an opportunity to exercise skills strong social component with an opportunity to learn from more skilled peers | regular practice aimed at skill developmentregular play as an opportunity to exercise skillsstrong social component with an opportunity to learn from more skilled peers |

| Private lessons: focused practice | regular practice and feedback aimed at skill development | regular practice and feedback aimed at skill development |

| Master Class | Feedback from outside professionals with emphasis on skill development | |

| Performances/games; competitions/tournaments | demonstration play with chance to test skills against peers | demonstration play; chance to test skills against peers |

| Opportunities to guide younger participants: | youth coach or ref | ? |

| Opportunities to observe others: | Games played by peers, Professional games, You tube videos of games and skills | Music played by peers Professional concerts, You tube videos of concerts and skills |

So what might an effective farm system for engineering talent look like?

Key ideas that came out of our discussion include:

- Programming/curriculum is aligned across grade levels so that students have a chance to build on skills they’ve begun to develop;

- Students and teachers are able to engage with industry expertise in the context of authentic projects. The easiest way for industry to participate is to have a clear ask– what expertise do you need when to do what. Having something concrete to respond to makes it much easier for a firm to see how well that effort aligns with their own goals for community engagement or talent development.

- Students are given the opportunity to practice in context. Students need multiple opportunities to run through the engineering design cycle on projects that matter to them.

- Students have a chance to prototype and work with materials throughout the design process and use that experience to refine their thinking about both the problem at hand and potential solutions.

- Projects are structured with a strong emphasis on process to help students resist the temptation to jump to a solution before understanding the problem, be willing to explore “riskier” ideas, and to aim for knowledge gain over “the right solution”.

- Students have informal opportunities to play with engineering in the same ways they might with music or sports.

- Students build technical skills in math and physics in concert with engineering design. PLTW is not a substitute for a math or physics class, but a complement to it.

- There is a community of practitioners working together to develop engineering talent. That community includes K-12 educators, university faculty, organizations that provide STEM programming, and industry expertise willing to work with students. Through ongoing collaboration, this community can build and strengthen the relationships that allow its members to find new opportunities for students.

What’s next?

Our next two Collab Labs provide opportunities to explore some of the ideas raised in this session. The March 12th session is focused on our Career Interviews project. We’re working with UWM and area high schools to prototype a process where students interview folks engaged in interesting work in Milwaukee. Beyond giving students a broader sense of what’s possible to do, we see this collaborative effort as an easy way for students to make an initial connection with folks in industry.

Our April Collab Lab will focus on tapping industry expertise. This will be an opportunity to take a deeper look at the types of engagements most valuable to educators and students, what makes that engagement worthwhile for both individuals and their employers, and what could help reduce the friction around matching expertise with educators who want to leverage it.

Join us for either or both sessions to share your perspective and ideas.

As we continue to digest what we heard at the session and in conversations that have continued afterwards, we have a couple of other ideas we’re exploring. Stay tuned or let us know if you’d like to get involved!

One more thing…

One of the folks I connected with as we planned Tuesday’s session was Shannon Smyth, the Youth Technical Director for the North Shore United Soccer Club. Shannon trains youth coaches in the methods recently adopted by US Soccer not just as a way to help students more rapidly develop technical skills, but to build broader participation and the creative talent of players coming up through the system. Shannon sees a lot of parallels between efforts to keep girls engaged in sport and those to keep them engaged in STEM. We shared an overview of the Play-Practice-Play model Shannon uses in advance of the session. You can find that here.