Last week’s Collab Lab served as a follow on from our November’s session on Place Based Engagement. At that session and in follow up conversations, Joe Kaltenberg, MKE Parks Manager with the The City of Milwaukee noted that input from students, residents, property owners, and other stakeholders can offer the department not only a clearer picture of the roles the playgrounds and parks oversee play in those neighborhoods, but also a richer vision of the roles they could play.

That prompted us to use Collab Lab 67 to explore how and where K-12 students might engage at different points in the City’s playground redevelopment process as a means to foster community input and engagement in those efforts. During the discussion participants identified three areas where engaging K-12 students could offer a rich experience for students and support key areas of the City’s process — stakeholder mapping, storytelling, and design.

Stakeholder Mapping

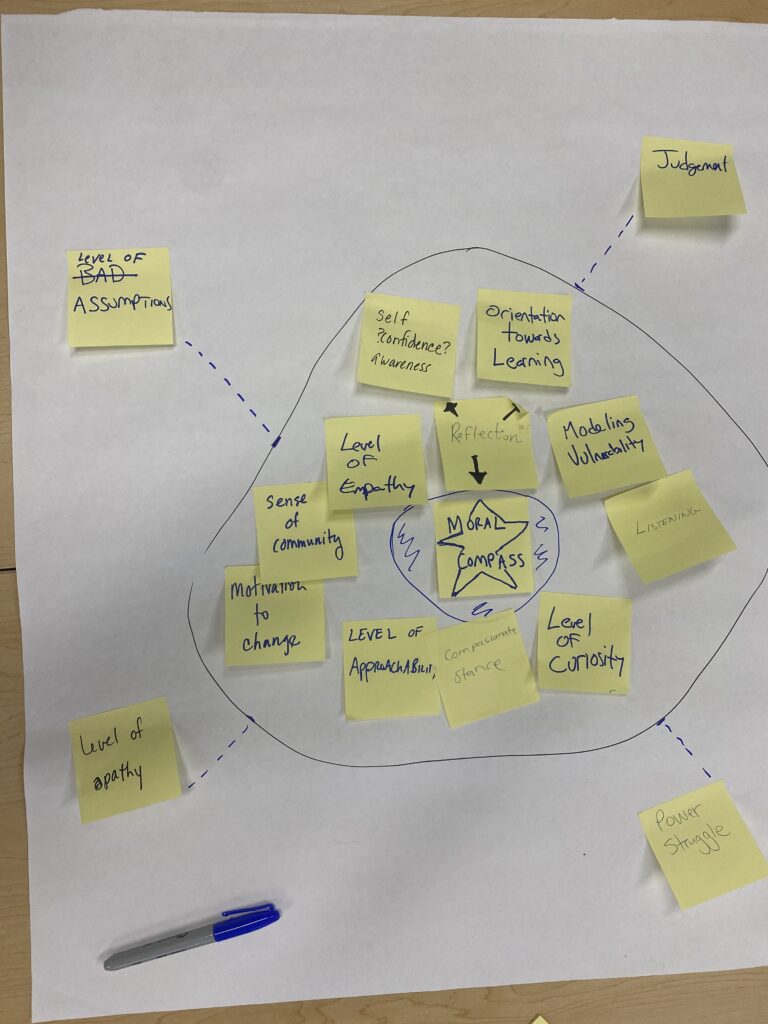

Stakeholder mapping allows the City to understand who uses, cares for, or is concerned with a particular playground or park, and who ought to have input or otherwise be involved as part of the redevelopment process. The work to identify stakeholders, their relation to a playground or park, the issues they see and the goals they have, is an opportunity for K-12 students to gain a much broader perspective on civic engagement. It’s a chance to understand who in a community cares about what happens on a specific site, the reasons behind that and where they may conflict and align with goals others may have.

Storytelling

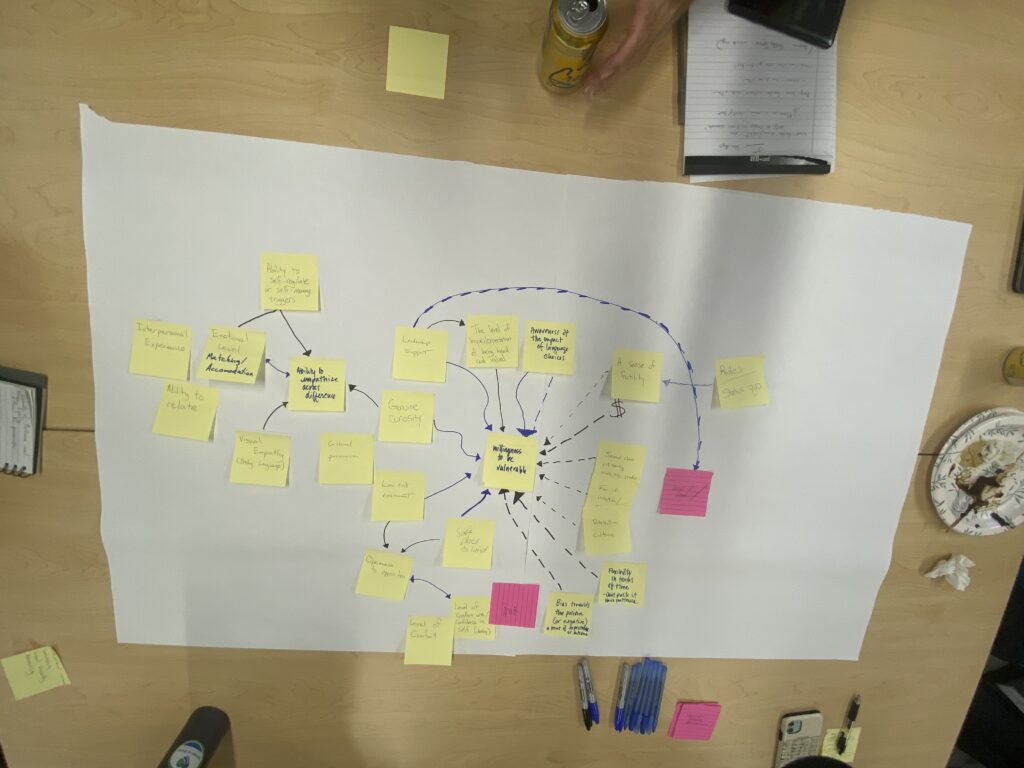

For a park or playground to be of the neighborhood in which it sits, the City needs to hear the stories of those who use, care, or are impacted by a park or playground, and what takes place there. Storytelling offers methods to understand where stakeholders are coming from and communicate those hopes, fears, and dreams to a broader audience.

Collab Lab participants noted that a storytelling event focused at or on a particular site would allow K-12 students to collect stories from a variety of stakeholders. It would also serve as a way to draw attention to that site as a candidate for redevelopment.

Ideation

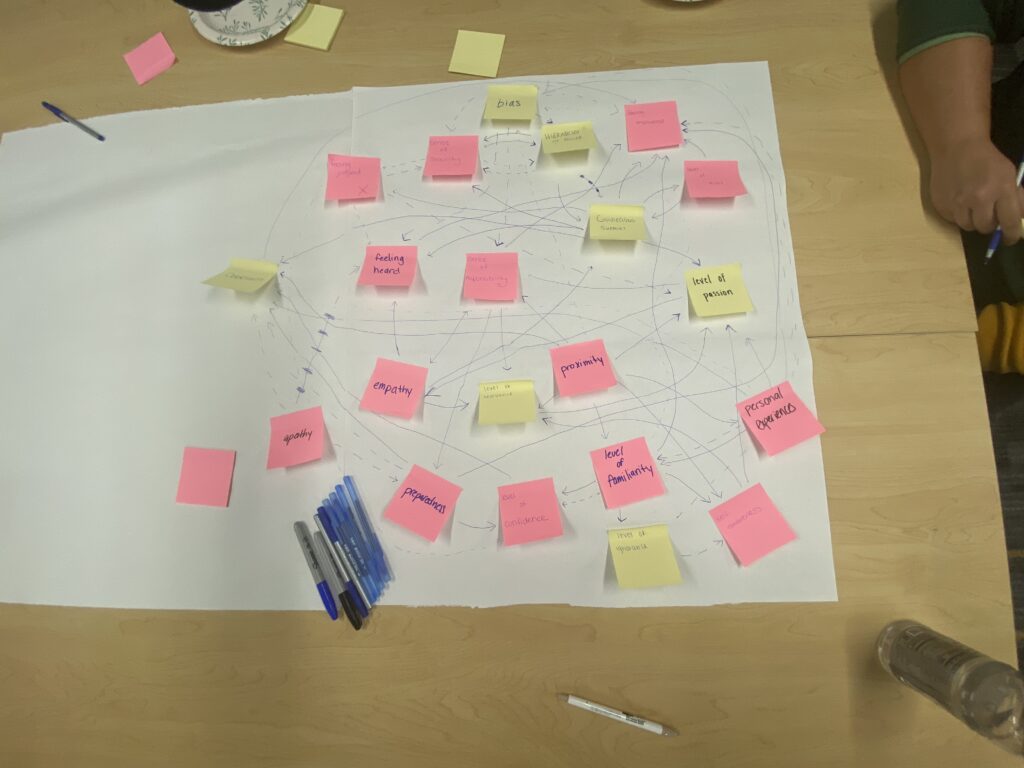

Involving students in the design of a playground or park, where they can see their ideas take shape and have an impact on the community is a wonderful idea. Yet, as Collab Lab participants noted, unless the process were constrained to proposals for the arrangement of pre-selected components, it is unlikely that they would ever see their designs implemented as envisioned, and even in this scenario, be able to recognize their contributions to what was put in place.

More importantly, this approach fails to leverage the fact that these are students. We shouldn’t be asking them to act as engineers, we should be asking them to dream, to think outside the box, and challenge the assumptions of engineers. Here the request of students ought to focus on how they or others experience a playground or the features or equipment under consideration. We ought to be asking them what adults involved in the process fail to see or understand about how a park or playground is experienced by those who use it. We need to probe behind suggestions for features that would never be implemented to understand the problem a student sees that an impossible feature solves.

Constraints

A common set of constraints cuts across all three of these areas for engagement. Central among them is the ability of teachers to effectively engage their students in this work:

- Finding the time to do so

- Establishing connections to curriculum standards

- Synchronizing school calendars with the City’s, particularly when the seasons and weather can further constrain the time students can spend on-site

- The availability of community partners to support student efforts

- The ability of teachers to collaborate across classroom or school boundaries for shared success

- The proximity of parks in the City’s pipeline to teachers and students ready to take on this work

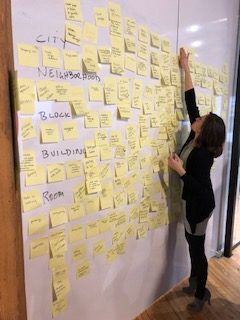

The Collab Lab did not provide an opportunity to dive into all of these issues, but we were able to identify a strategy in one area. Most schools, particularly at the middle and high school level draw students from well beyond the neighborhood in which the school sits. Thus, while a park or playground may be near a school, many students will have limited exposure to it or be able to access it outside of school hours. For any of the opportunities noted above, this limits the ability to rely on students themselves as stakeholders, storytellers, or users of their own designs.

What we can do is ask students to work at a higher level, to be the mappers of stakeholders, the collectors of stories. We can ask them to be the designers who can communicate what the users of a park or playground that is near their school want from it or hope that it could become.

Where do we go from here

The work to organize teachers, students, and community stakeholders to participate in the planning process would be a lot for MKE Parks to take on. While useful to have that input, it’s not really something for them to take on. We’re exploring with Joe a different approach– developing a framework that, recognizing the timelines and constraints faced by each of these participants, allows them to work outside of a City managed process while offering their input and results of their work at the most useful points in the process. We plan to spend time between now and the end of the school year to understand what this framework would need to look like to make this work for educators. If you are interested in participating in that process, let us know.

We started the conversation by asking participants to describe for their tablemates a public space that holds meaning for them. We then asked each group to identify the what helped create that sense of meaning. Across our discussion groups, several key themes emerged:

We started the conversation by asking participants to describe for their tablemates a public space that holds meaning for them. We then asked each group to identify the what helped create that sense of meaning. Across our discussion groups, several key themes emerged:

We’re in our second year of a working with

We’re in our second year of a working with